The real estate market is starting to show signs of cracking in some of the most expensive cities in the country, and other pricey areas should brace for a rough stretch ahead.

In the early part of the year, the prevailing real estate narrative suggested that housing prices would stay buoyant because of a historic shortage of available inventory even as mortgage rates surged. But for all the signs that the market was facing headwinds, few people were prepared for mortgage rates that approached 6% recently, which put monthly payments out of reach for many buyers.

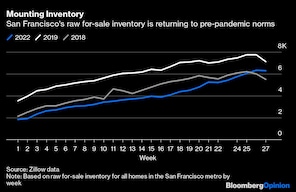

What’s more, housing supply varies widely across the country, and sellers are sensing a closing window of opportunity to lock in profits, rushing additional inventory into the market.

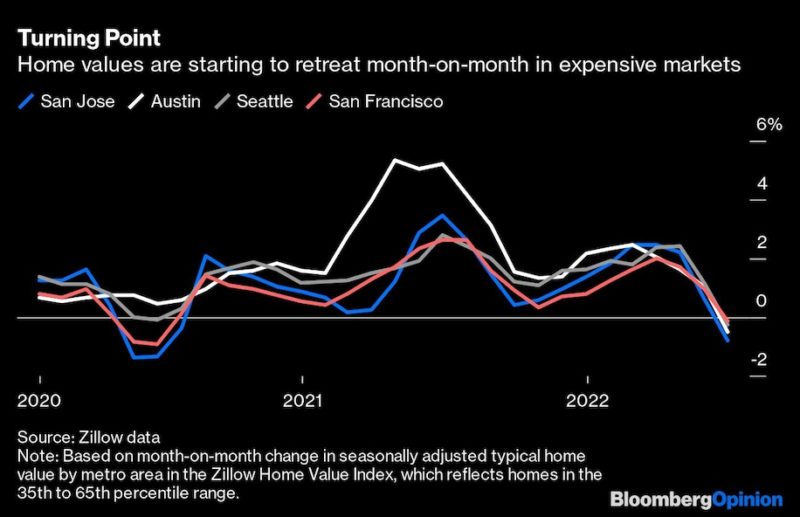

The upshot is that the market is already starting to turn in some places. On a seasonally adjusted month-on-month basis, home values fell in June in seven of the 100 biggest housing markets, four of which are in California, plus Austin, Texas; Seattle; and Ogden, Utah, according to Zillow data.

The real estate market is starting to show signs of cracking in some of the most expensive cities in the country, and other pricey areas should brace for a rough stretch ahead.

In the early part of the year, the prevailing real estate narrative suggested that housing prices would stay buoyant because of a historic shortage of available inventory even as mortgage rates surged. But for all the signs that the market was facing headwinds, few people were prepared for mortgage rates that approached 6% recently, which put monthly payments out of reach for many buyers.

What’s more, housing supply varies widely across the country, and sellers are sensing a closing window of opportunity to lock in profits, rushing additional inventory into the market.

The upshot is that the market is already starting to turn in some places. On a seasonally adjusted month-on-month basis, home values fell in June in seven of the 100 biggest housing markets, four of which are in California, plus Austin, Texas; Seattle; and Ogden, Utah, according to Zillow data.

These places have several common characteristics. First, they all became expensive either in dollar terms, in relation to local household incomes or both. Second, the much-touted inventory shortfalls weren’t as dire to start with, and some of them have begun to return to a semblance of normal levels, erasing the scarcity cushion that was supposed to buttress prices.

Finally, many of them are related to the US tech and startup ecosystem, which faces layoffs as well as the effects of a sharp drawdown in share prices that curbs the value of stock-based compensation and employee wealth. Silicon Valley wasn’t exactly the prime example of the pandemic housing boom — that was Sun Belt communities and smaller cities in Utah and Idaho — but prices surged there nevertheless and from an already high starting point in 2019.

It stands to reason that US housing prices would come under pressure in this economy. Much like consumer prices, stocks and even cryptocurrencies, home prices surged during the Covid-19 pandemic, and now those sky-high prices are running up against a Federal Reserve committed to stabilizing inflation by tightening financial conditions. If the Fed overdoes it, it risks pushing the economy into a recession, which would certainly hurt real estate further.

Yet with inflation expected to rise to another 40-year high in the consumer price index report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Wednesday, the Fed’s policy rate is likely to keep climbing, and mortgage rates could be elevated for the foreseeable future. Buyers who remember the average 13% mortgage rates of the 1980s might not think the current 5.3% is so bad, but when combined with expensive house prices, it has made homeownership untenable for many. Last week, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard suggested that an adjustment in housing prices would be natural:

It wouldn’t surprise me if we have to cool off some in the housing market. I mean that was a boom – an absolute boom in the last two years – in housing, and even now I’m not so sure that the prices are really coming off, at least in the aggregate statistics.

When a Federal Open Market Committee voter says the housing market might have to “cool off,” it’s worth listening to.

Of course, national home values are still increasing for the time being, thanks in part to those inventory restraints that don’t look as if they will resolve themselves soon. On the one hand, housing is a slow-moving market in which sellers are reluctant to accept that they can’t get the same price that their neighbors did in the recent past. Transaction volumes are clearly cooling, and that should eventually feed into prices, at the very least cooling price appreciation by the end of the year.

On the other hand, home prices are part of the inflation measures that the Fed tracks though a component called “owners’ equivalent rent,” and their resiliency could encourage the Fed to push up interest rates even higher. It’s a losing battle either way.

That isn’t to say that the broad market is poised for a 2007-like crash; it probably isn’t. Lending standards have vastly improved since then, and it seems unlikely that many homeowners will find themselves forced to sell. Yet with some key markets already slipping, it would be foolhardy to assume that the rest of the housing market couldn’t end up in a similar position soon as long as the Fed remains committed to tight financial conditions. The run-up in prices has been stunning, and it’s only logical to suspect that they could go in reverse for a while.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company’s Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.

Source: washingtonpost.com